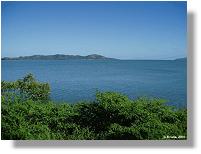

| The marine coastal area along the Esplanade at the Kissing Point end

of Rowes Bay (Figure 1) is very shallow, with an area of several

square kilometres being exposed to the air during spring tides.

|

| Figure1. View of Rowes Bay from

the Esplanade near Kissing Point - high tide |

This intertidal area includes several different marine habitats such

as a mangrove forest (Figure 2), a rocky shoreline (Figures

3a & b), a small muddy estuarine creek (Figure 4), coarser

sandy flats (Figure 5) and several rubbly reefal areas, one of

which includes a tropical sponge garden on the seaward edge (Figure

6).

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Students exploring the

mangrove forest at Rowes Bay during low tide |

|

Figure 3a Rocky shoreline (Rowes

Bay) at low tide |

|

|

|

| Figure 3b. Rocky shoreline (Kissing

Point) showing JCU students calculating tide levels |

|

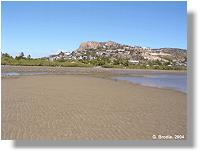

Figure 4. Muddy creek area at high

tide |

|

|

|

| Figure 5. Muddy sandflats exposed

at low tide |

|

Figure 6. Rubbly reefal areas exposed

when the tide is very low |

Collectively these habitats are home to thousands of different types

of marine invertebrates (animals without a backbone) and each individual

habitat contains its own specialised suite of fauna and flora that is

well adapted to the environmental conditions found there.

Some of the invertebrates living on the intertidal area at Rowes Bay

are large and easy to see, whereas many others are smaller and very good

at hiding. Some are motile and able to move from one habitat to another,

while others are sessile and unable to move to a more favourable area

should conditions change or predators threaten. Some species are present

in large numbers while others are more solitary – perhaps even with

their presence changing seasonally.

Although a few local scientists are aware of the high level of invertebrate

diversity in this area, the fauna has never been systematically and collectively

documented and we therefore do not know exactly how many marine invertebrate

species are to be found in this intertidal area.

This website, which is part of the Townsville City Council Natural Assets

Database, aims to begin the huge task of documenting the wide variety

of invertebrate animals found in the intertidal area at the Kissing Point

end of Rowes Bay.

If you would like to contribute to this website in any way please contact

the Environmental Services section of the Townsville City Council (add

website link) or Dr Gilianne Brodie, at the Department of Marine Biology,

James Cook University (47814280).

Below is a small sample of the marine invertebrate fauna found in each

of the habitats discussed above:

| MANGROVE

HABITAT |

|

|

| Figure 7. The mud crab Scylla

serrata |

Figure 7: Some crabs are very large and easy to see while others

are smaller and often very cryptic. The size and structure of a crab’s

front claws provides a good indication of their feeding habits. Tiny

pinchers can indicate a plant feeding herbivore while the large claws,

as seen on this mud crab (Scylla serrata); indicate a more

aggressive predatory lifestyle.

|

| Figure 8. The arboreal mangrove

snail Littorina |

Figure 8: Many different types of animals live in the mangroves

at Rowes Bay - some hide by burying in the sediments while others,

such as the arboreal snail (Littorina) shown here, live in

mangrove tree branches. The shells of these tree-dwelling snails are

very light in comparison to ground dwelling (benthic) snails making

it easier for them to carry their protective shell “home”

around with them when climbing. |

| ROCKY

SHORE |

|

|

| Figure 9. Oysters Saccostrea

echinata |

Figure 9: Several different oysters can be found attached to

the rocks at Rowes Bay. Such oysters are bivalve molluscs (with two-shells)

that are able to cement one of their protective valves to hard substrates.

This means that oysters like the Saccostrea echinata shown

here are sessile and therefore unable to move around as adults.

|

| Figure 10. The tiny but numerous

Nodilittorina snails |

Figure 10: Animals that feed on algae, such as the herbivorous

snail (Nodilittorina) seen clustered together here, are a cryptic

but very important part of the rocky shore habitat. Although tiny

(<10 mm) they are present in very large numbers and the rocky surfaces

high on the intertidal area would look very different (covered in

green algae) if these animals were not present. |

| ROCKY

RUBBLE HABITAT |

|

Figure 11a & b: Seahares like the Aplysia dactylomela seen

here are relatively large shell-less molluscs that are seasonally

common in tropical coastal areas. This species is well known for

is spectacular behaviour of releasing bright purple ink that functions

as a deterrent or a distraction to predators such as fish, crabs

or humans. Seahares play an important role in many coastal habitats

because of their habit of periodically occurring in large numbers

and their ability to consume large amounts of macroalgae, including

the toxic cyanobacterium Lyngbya.

|

|

|

| Figure 11a. Seahare Aplysia

dactylomela |

|

Figure 11b. Seahare inking

when disturbed |

|

| Figure 12. Feather star |

Figure 12: The feather star shown here is a very primitive

member of the phylum Echinodermata and not often seen in intertidal

coastal environments. It is related to the starfish and sea urchins,

which are more commonly seen by reef visitors. This feather star is

nocturnal (active at night) and normally lives in deeper water offshore.

However, it is sometimes washed into intertidal areas like Rowes Bay

by storms and bad weather. |

| CREEK

& FINE MUD |

|

| Figure 13: The proboscis (feeding

organ) of an echiurian worm |

Figure 13: The fine mud around the creek bed provides a suitable

home for several different worm species. Although often unattractive,

worms play a vital role in aerating and mixing the fine sticky sediment

allowing a broader range of organisms to exploit the habitat’s

resources. Most of these worms are cryptic and live buried in the

fine sediment with only their soft feeding structures visible above

the substrate. One of these worm species is the echurian and with

careful observation its long translucent proboscis (feeding organ)

can be seen here laying over the surface of the sediment. |

| SANDY

FLATS |

|

| Figure 14: Bivalve mollusc

Periglypta |

Figure 14: Many different bivalve molluscs can be found within

the Rowes Bay intertidal area. One of the largest ones (Periglyta

chemnitzi) is difficult to find alive because of its excellent

burrowing ability, however the hard shells left behind after it dies

clearly indicate its presence in the soft sandy and muddy habitats.

|

| Figure 15: Tube dwelling polychaete

worm Diapatra |

Figure 15: Diapatra is a relatively large polychaete

worm that makes its own flexible silky tube within the sandy flat

environment of Rowes Bay. However, only the very distinctive tip of

this tube can be seen above the surface of the substrate. Like many

burrowing animals Diapatra is very fussy about the type of

sediment it lives in. If the sediment composition changes too much

the next generation of animals will not survive in the same place. |

| OUTER

REEFAL AREA |

|

| Figure 16. Unknown sponge |

Figure 16: Many different species of sponges can be found in

the intertidal area at Rowes Bay. Although often colourful, like the

yellow sponge seen here, these colonial animals can be difficult to

identify. Sponges feed by filtering large volumes of seawater and

extracting the digestible material from it. The species found at Rowes

Bay cope surprisingly well with the turbid muddy conditions that surround

them.

|

| Figure 17 : Nudibranch seaslug

Cuthona yamasui |

Figure 17: There are thousands of different types of shell-less

marine seaslugs (nudibranchs) found worldwide. The species shown here

was found among the rocky rubble of the outer reefal area at Rowes

Bay. Its scientific name is Cuthona yamasui and it was first

described from Japan in 1993. This specimen is about 45 mm long and

feeds on bryozoans (small colonial animals) also found in the same

habitat. Bryozoans, and the animals that prey on them, are very important

marine organisms because they are part of “fouling” communities

that initially cover human-made marine structures such as jetties

and boat hulls. Control of such fouling organisms is a very “hot”

topic in marine biology because it strongly relates to the economic

efficiency of our boats, ships and harbours. |

|